HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL CHARACTERIZATION

The quilts from Castelo Branco occur with a singular abundance all over Beira Baixa, but are only perceived as a unique and precious set at the end of the 19th century, when King D. Carlos and Queen D. Amélia visit the city.

In fact, for the inauguration of the Beira Baixa Line in September 189I, the city of Castelo Branco not only festively decorated its balconies and windows, but, to accommodate Their Majesties, the Palace where the Provincial Council used to be, was all furnished and decorated with the best the city could offer. Thus, dozens of bedspreads appear together, used both outside the buildings and inside the Palace to cover walls and frame doors and windows, forming a rich and unusual set that caught the attention of the Queen"(. . .) who was very pleased when told that these works represented an (old) industry of Castello Branco," as one newspaper of the time put it.

António Roxo, who witnessed and reported the Queen's admiration, is the first to use the expression "Castelo Branco bedspreads" in an article published on October 25th, 1891, because the Queen's look, her "special attention" to the bedspreads, allowed her to have another perception, another understanding of that set of pieces that so many in the region owned and that, being so common, no one realized how unique and extraordinary they were.

However, it was only in June 1929, at the 6th session of the IV Beirão Congress, that quilts and their embroidery entered Castelo Branco's agenda. In this session, Maria Júlia Antunes presented the communication, "Rendas e Bordados da Beira", dedicating one third of her exhibition to the embroidery generically called "a frouxo", as the Castelo Branco bedspreads embroidery was then called. For the first time there is a text describing the colors, the stitches used and the organization of the various types of drawing of the Castelo Branco bedspreads. At the end, Júlia Antunes emphatically calls for the protection of "popular industries" and the importance of re-launching them.

A few months later, in October, with the intention of writing a more developed article about the quilts of Castelo Branco, which unfortunately did not happen, Júlia Antunes returns to the city where she observes about 30 quilts. Manuel Paiva Pessoa, former director of the Francisco Tavares Proença Júnior Museum, accompanied her on this visit. He then published a text in the Terra da Beira newspaper about this meeting and the work developed at the time, bringing Maria Júlia Antunes' theses to many more people, which he himself takes up and endorses.

In essence, it was considered then that the quilts with a more frustrating design, without a defined bar where open carnations constitute the essential decorative motifs would be the oldest, made within the "popular classes". These "plebeian" bedspreads would have caught the attention of the ladies of the manor houses, who would have enriched them with a more careful design and a greater variety of motifs, so that the "patrician or manor house" bedspreads would have been not only more sumptuous and careful, but also more recent. And if Júlia Antunes, on quilts, stresses that it is "a notable industry, now painfully extinct, which was born in the city of Albicastrense," Pessoa ends by writing, "It is, therefore, time to think seriously about restoring this industry.

At the time, embroidery in loose silk on linen, continued, however, to be done, integrating the curricula that the city's schools provided for the girls whose social condition allowed them to attend them. As Paiva Pessoa writes: "In the National and December 1st Colleges of this city, many of these quilts have been embroidered, and other ladies also embroider them.

However, according to what Júlia Antunes, a demanding teacher of needlework, wrote, it is a poor quality embroidery, made in a domestic context or for apprenticeship: "it must be admitted that the technique of primitive quilts has been distorted, in its essential characteristic elements, (...) and, if it is not followed by a well oriented study of what is still known of the old, (...) there is the danger of seeing an art of great beauty totally lost or disfigured". Paiva Pessoa adds: "No extravagant futurism. It is necessary that the bedspreads have the features of the old ones. It would also be very convenient if the silk, using national silk, was dyed using the old Portuguese dyeing processes, with unalterable vegetable dyes.

In fact, aware as to the possible problems in the revival they advocate for embroidery, both are still concerned with the design, with how the silk is dyed, with the choice of colors to be used, and with the embroidery "method" itself.

This situation continues for the next ten years, but it is during this time that the prestige and cultural protagonism of Eurico Sales Viana is definitely established. In 1936 he had been part of the provincial jury that selected the candidate villages to be the most Portuguese Village in Portugal (the contest of the Secretariat of National Propaganda, directed by António Ferro) and, with the national victory of Monsanto (municipality of Idanha-a-Nova, district of Castelo Branco), of which he is one of the main promoters, his political weight is reinforced, so much so that, together with the ethnographer Luís Chaves, he is the one who prepares, during 1939-1940, the part of the Exhibition of the Portuguese World (held in Lisbon in 1940), dedicated to the "ethnography of the metropolis.

To this end, Sales Viana, accompanied by Luís Chaves, travels through Beira Baixa during the month of July 1939, seeing and appreciating more than a hundred quilts. It is not surprising that on August 5 he publishes, in the weekly newspaper "A Beira Baixa" (no. 121), the text "As Colchas de Noivado" (The Engagement Quilts), an article with such success that a reprint is soon made to ensure a wider dissemination.

In this text, the quilts of Castelo Branco are understood as "engagement quilts" and both Sales Viana and Luís Chaves coincide in the same discourse on quilts, strongly conditioned by the ideological values they both share.

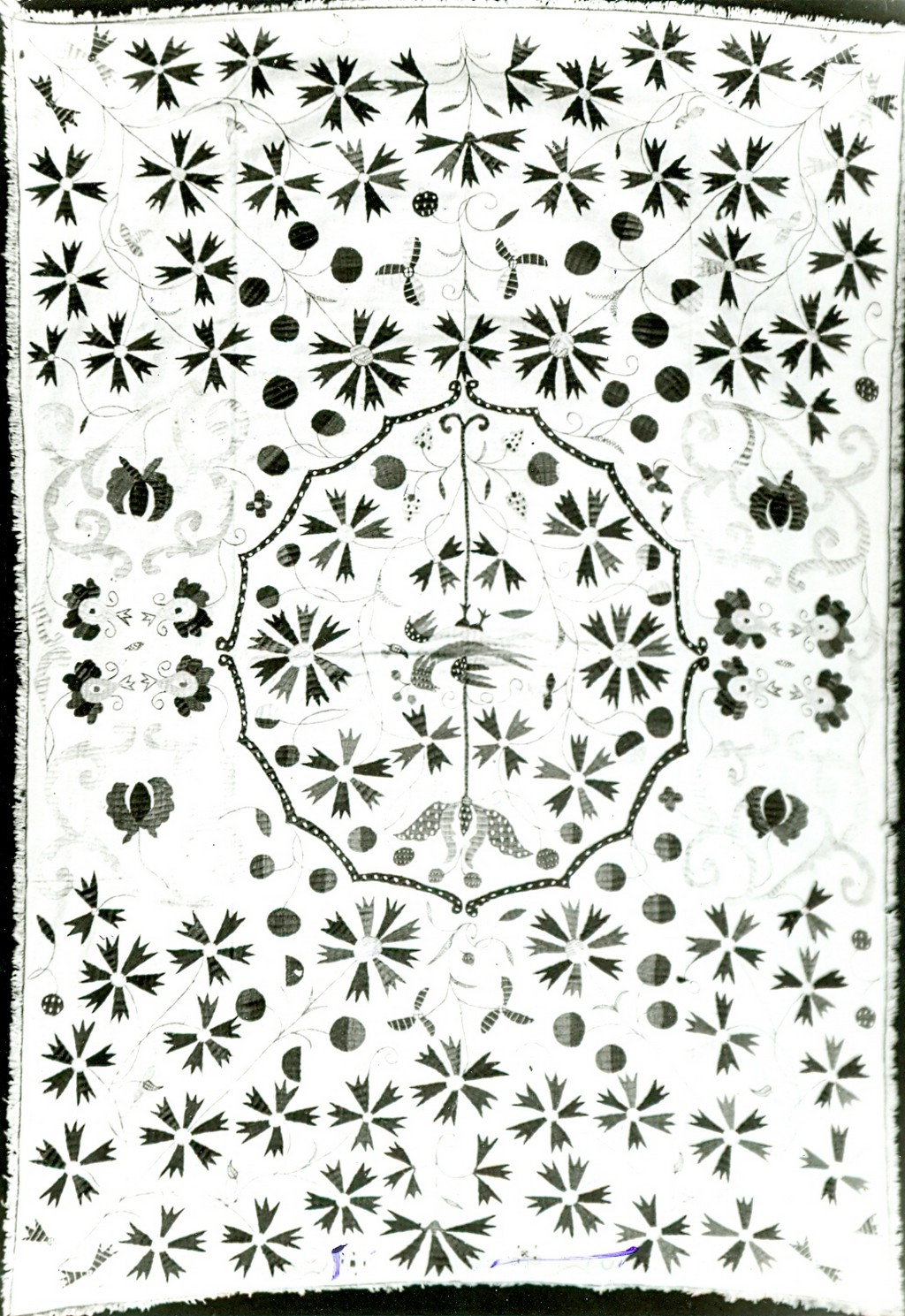

The bedspreads, they write, are unique pieces that single, virgin girls embroider on linen that they themselves have spun and woven, and on silk that they have produced, for the purpose of being used only once, on the day of their espousals, after which they would be put away. Both insist on the importance of the symbolism of the motifs decorating the quilts in which "pomegranates, pine cones, and bunches sing hymns to the Family Union"; "(the) lilies are joyfully manifested in an apotheosis to Virginity", or "(the) stylized cocks allude to the phallic virtue of Virility", obvious examples as to the ideological nature of this discourse, which translates a specific vision of the family that the regime of the time defended and promoted.

It was also in 1940 that the President of the Provincial Council, Father Ribeiro Cardoso, worried about the economic situation, founded an Embroidery School of the Province of Beira Baixa, seeing in the re-launch of the embroidered bedspreads production a chance to create employment. With the artistic supervision of Sales Viana and with Deolinda Riscado as embroidery teacher, the School begins to function. However, Ribeiro Cardoso soon realizes the difficulty in obtaining the natural silk needed for the embroidery of Castelo Branco, now that World War II is raging throughout most of Europe, so he promotes a major campaign of planting mulberry trees as a means to obviate the lack of silk. The campaign starts, but the cyclone in February 1941 destroys not only the young plantations but also many of the existing mulberry trees, so the School ends soon after, in August.

Meanwhile, in the context of the Commemorations of the Centenaries (1140 and 1640), exhibitions were held all over the country praising the most iconic productions of each region. In Castelo Branco, in 1941, there was an extraordinary exhibition of quilts, almost one hundred, which mobilized the attention of the local elites, to such an extent that the following year some of these quilts were exhibited in Lisbon by initiative of the Secretariat of National Propaganda, and which the magazine Panorama disseminated to a wider public.

In 1945 another article appears in the magazine Panorama, while Maria José Mendonça, with the collaboration of Maria Clementina Carneiro de Moura publishes, in the same year, in the Catalogue of the MNAA's 5th Temporary Exhibition, the article "Colchas Bordadas dos séculos XVII e XVIII", where examples of the quilts from Castelo Branco are presented.

In five years, the recognition of the quilts of Castelo Branco had gone beyond the local and regional sphere. The quilts and their embroidery were now known to an elite eager to obtain them. Thus, while articles and exhibitions followed one another, the existence of production workshops was also promoted, which, by meeting the demand created, would allow for their sustainability.

Since 1939, at the Colégio de Nossa Senhora de Fátima, an embroidery workshop sponsored by the Mocidade Portuguesa Feminina (Portuguese Feminine Youth) tried to meet the market's demands. However, the lack of silk and the difficulty of selling an expensive product led to its closure in 1945.

It was only in the early 1950s that the Oficina Casa-Mãe appeared, which, founded by Elísio José de Sousa, produces, publicizes, and successfully sells Castelo Branco bedspreads to a market that is no longer just local, but national, and even international. Elísio José de Sousa's vision and perseverance lead him to dedicate himself to the mission of producing the quilts of Castelo Branco for which he promotes exhibitions in many Portuguese cities, but also in cities such as London, Paris, Milan, S. Paulo, and Luanda.

The prestige of the Mother House has even led the government to order quilts there, which are offered to very important personalities on official visits to our country, such as Queen Isabel II, her sister Princess Margarida, or the wife of the President of Brazil.

These two workshops, Centro número 2 da Mocidade Portuguesa Feminina and Casa-Mãe de Elísio José de Sousa, are responsible for the training of the most distinguished embroidery masters who, over the years, have taught hundreds of girls who, in turn, have passed their knowledge on to others. Those who were part of the MPF workshop ended up, in 1976, integrating the staff of the Francisco Tavares Proença Júnior Museum. The Motherhouse closed its doors in 1969 due to the death of its founder. But the knowledge of its embroiderers has borne fruit in the many workshops that, with greater or lesser difficulty, have maintained until today the production of the Castelo Branco embroidery.

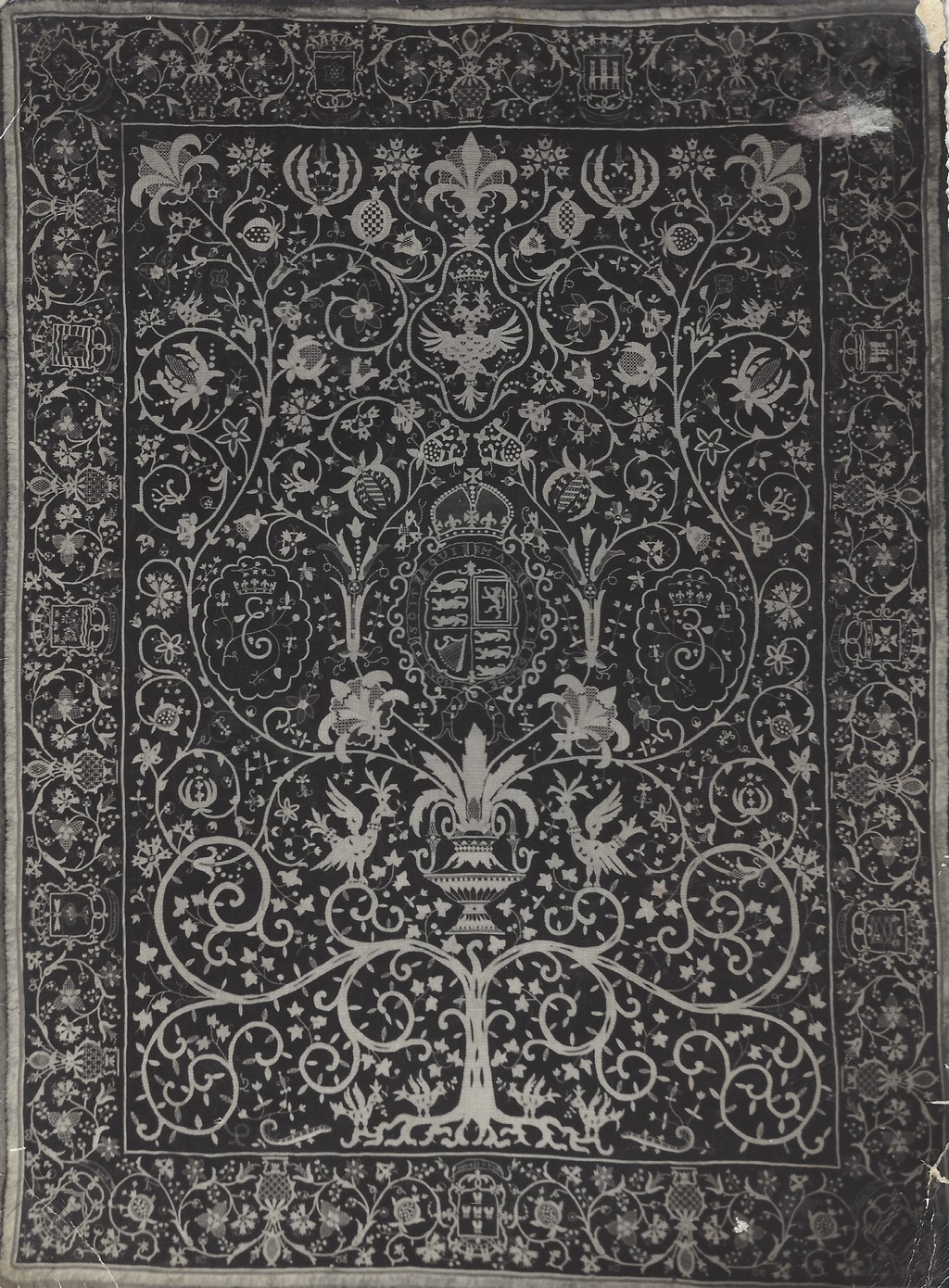

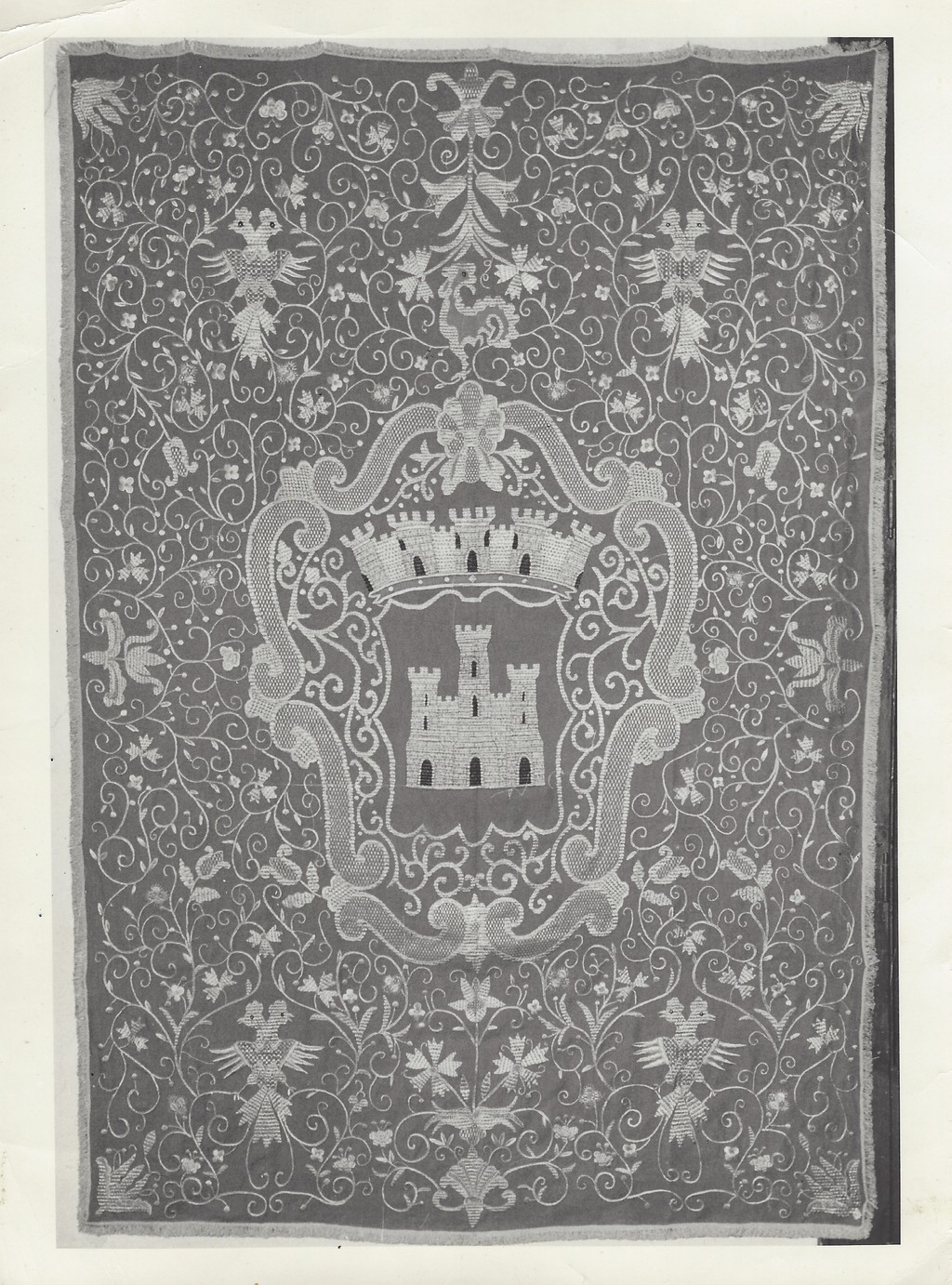

Since 2008, a significant group of quilts, until then considered to be from Castelo Branco, are now seen as having been produced in Lisbon. In fact, they are not quilts, but armoring cloths, because their length is always more than 280cm, and some exceed 300cm. In addition to their size, these pieces are also distinguished by their decorative program, with a distinctive bar and a field occupied by a repetitive pattern, in stripes, as in a tile pattern. Besides the dense design and great perfection, these pieces are characterized by the rigor of their embroidery, and in almost all of them there is even an embroidery stitch, difficult to execute (the "galão de malha" stitch that the embroiderers call "ponto recuperado"), which was only used in Portugal in the late 17th century, beginning of the 18th century, and which does not appear in any other country.

The open carnation quilts, because of their looser, almost sloppy design, seem more compatible with their production in the Castelo Branco area.

There is also a third group of quilts, characterized by their careful, unstitched design, centers with various types, which may or may not have been embroidered there.

The definition of these three groups corresponds to what the scientific community currently considers to be the origin of the Castelo Branco bedspreads.

However, for the case of the Castelo Branco Embroidery, these distinctions do not hold, once since the middle of the XX century, in the process of re-launching the production, all these pieces were considered as models of the embroidery that, in the meantime, was being produced. As a result, the range of patterns and motifs has expanded considerably. Since what is being certified is embroidery and not a typology of pieces, it doesn't even seem sensible, after all this time, to want to reconcile the embroidery of Castelo Branco to that more restricted matrix, based solely on the pieces that, with little or no doubt, are effectively considered to have been embroidered in the region centered around Castelo Branco.

Thus, more than 80 years after the re-start of the workshop production of the Castelo Branco Embroidery, it is then, possible, another criticism and distancing, so we should distinguish between "Colchas de Castelo Branco" and "Bordado de Castelo Branco". The first expression covers the set of historical pieces, produced essentially in the 18th century (those dated from the end of the 17th century were not made there, but in Lisbon). Of these pieces, there is the possibility that some may not have been produced in Castelo Branco. However, in the current state of our knowledge, this is not possible to claim. Nor to infirm.

The Castelo Branco's embroidery, an activity that for eighty years has mobilized in the city and region, many hundreds of embroiderers, corresponds to a production of natural silk embroidery on linen, made according to an eclectic set of models, worked in a very loose way, because we rarely see copies, but reinterpretations of the existing models, being frequent the mixtures of motifs of various types.